The Forgotten Journeys: A Tale of Displacement and Belonging

When the British abolished slavery, they and the other colonial powers needed a new source of cheap labor they could exploit. They came up with the idea of indentured labor. This was slavery with a legalised face, a hypocritical fig leaf under which the British pretended to be humane and occupy the higher moral ground. This is the tale of people, forgotten by their own. The Indian Tamils.

HISTORY

The harsh winds of circumstance blow families across continents, scattering seeds of belonging that struggle to take root in foreign soil. My father's story began in those tremulous years between the great wars, when poverty stalked the land like a merciless shadow. His family, once rooted in the red earth of Tamil Nadu, watched their fortunes crumble like ancient temple walls weathered by time.

At barely sixteen, still carrying the softness of boyhood in his eyes, my father made the wrenching decision that would define generations. The Royal Indian Navy beckoned—not with glory or adventure, but with the stark promise of survival. He left behind the familiar cadence of Tamil voices, the scent of jasmine that perfumed evening prayers, and the ancestral soil that had known his forefathers' footsteps for centuries.

From my father's younger siblings, whom he raised with hands still tender from his own childhood, I gathered fragments of this exodus. Their voices carried the weight of necessary migration, of leaving behind a homeland that lived on in their dreams but could no longer sustain their bodies. We became a family of wanderers, carrying Tamil Nadu in our hearts while our feet learned the rhythms of distant shores.

This rootlessness flows through my veins like an underground river. I wear many identities—Indian, Mumbaikar, Keralite, IOCian—each one a thread in the tapestry of who I am. My Keralite heritage, inherited through my mother's lineage, wraps around me like a familiar shawl, warm and comforting. Mumbai's relentless energy pulses through my urban soul. Yet fragments remain scattered, pieces of a puzzle that never quite forms a complete picture.

But when I step into our village temple in Tirunelveli district, when the ancient stones recognize something ancestral in my presence, peace descends like monsoon rain on parched earth. In those sacred moments, the scattered pieces align, and I touch something eternal that transcends the accidents of geography.

I am fortunate—blessed to remain within the embrace of my motherland, able to journey back to these roots whenever longing overwhelms me. Kerala nurtures the maternal part of my soul, offering belonging when displacement threatens to untether me completely.

Yet recently, I encountered a story that threw my own gentle displacement into stark relief. A Tamil from Sri Lanka shared his family's odyssey—a narrative so searing it seemed to burn the very air between us. His great-grandfather, torn from the familiar soil of Tamil Nadu like a tree uprooted in a storm, was swept away by the British tide of indentured labor to toil in Sri Lanka's misty hill plantations.

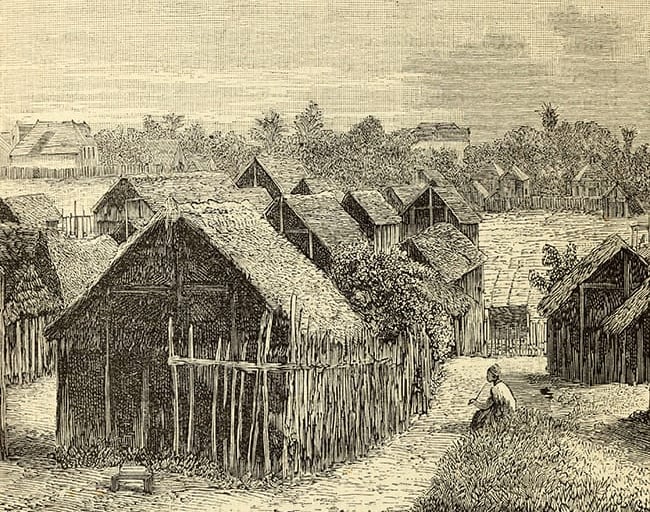

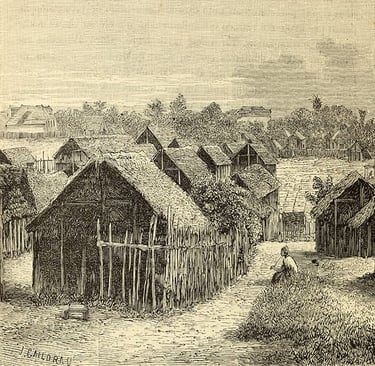

The British came with honeyed promises and bitter realities. They spoke of opportunity while shackling souls to contracts that differed from slavery only in name. These Tamil laborers, my countryman's ancestors among them, poured their sweat into foreign soil, believing they were planting seeds of belonging. They built roads that connected distant villages, cultivated tea gardens that painted the hills emerald green, and constructed the very infrastructure that would outlive their hopes.

For generations, they believed themselves stakeholders in this island nation they had watered with their tears and strengthened with their sacrifice. Sri Lanka was to be their adopted mother, Tamil Nadu their distant but unforgotten motherland. They raised children who knew no other home, who dreamed in Sinhala and Tamil both, who considered the island's mountains as familiar as their ancestors' plains.

Then came the cruelest betrayal of all. The very land they had nurtured turned against them. Citizenship became a mirage, voting rights evaporated like morning mist. They found themselves orphaned by the nation they had helped build, rejected by the very soil their labor had enriched. They became the unwanted children of their perceived mother, standing at the threshold of a home that no longer recognized them.

In their anguish, they turned their eyes toward India—the motherland that lived in their songs, their prayers, their memories passed down like precious heirlooms. Surely India would embrace these lost children, would recognize the Tamil blood that flowed in their veins.

But even this hope crumbled like ancient clay. When some finally made the journey back, India received them not as returning children but as inconvenient reminders of a history better forgotten. They were dispersed to remote forests and hill stations in Tamil Nadu and Kerala—places like Nelliyampathy, where isolation wrapped around them like a second exile.

Here, in these green prison of hills, they found themselves once again reduced to little more than indentured laborers. They worked for wages that mocked their dignity, lived in conditions that tested their endurance, yet clung to the slim consolation of citizenship and voting rights—papers that proclaimed their belonging even as their daily reality whispered of continued displacement.

Still, they persevered. With hands that remembered the art of survival, they carved out new lives from reluctant soil. Their children, inheritors of multiple displacements, slowly climbed toward better tomorrows, each generation reaching a little higher than the last.

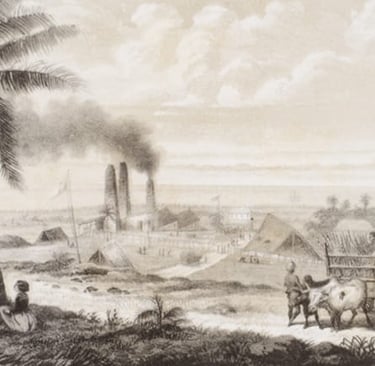

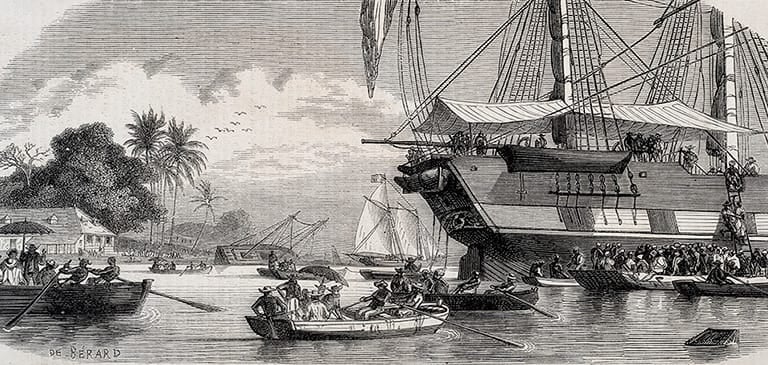

This encounter awakened me to a vast ocean of forgotten stories. Across the seas, scattered like stars in a dark sky, live the descendants of countless Tamils who were swept away by imperial currents. The British Empire, having ended the slavery trade, still hungered for bonded bodies to fuel its colonial machinery. They found their answer in indentured labor—slavery dressed in legal clothes, bondage wrapped in contracts and false promises.

The French, not to be outdone in this trafficking of souls, plucked people from their own territories like Pondicherry, sending them across oceans to plantations that would consume their lives.

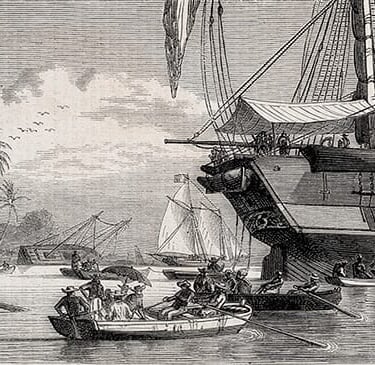

The voyages themselves were odysseys of suffering. Ships packed with human cargo sailed for months, sometimes over a year, carrying their desperate passengers through storms of sea and spirit. In cramped, fetid holds where disease spread like wildfire and hope dimmed with each passing day, how many souls were lost to the depths? How many bodies were committed to oceanic graves while families back home still lit lamps for their return?

The survivors who reached distant shores carried scars that would never heal, memories of a homeland that grew more mythical with each passing season. They planted their sweat in foreign fields, raised children who would speak in tongues their grandparents never knew, and watched their Tamil heritage slowly dilute like ink in ocean water.

Today, their descendants are scattered across continents—in Mauritius, Fiji, Malaysia, South Africa, the Caribbean islands—carrying fragments of Tamil culture like precious seeds that somehow still sprout in alien soil. Yet their stories remain largely untold, their struggles unacknowledged by the very nation that gave them birth.

Where were the voices raised in their defense during India's freedom movement? Where were the leaders who spoke eloquently of independence and justice when these lost children cried out across the seas? Even after independence, when India took her place among nations, these scattered Tamils remained invisible, their pleas echoing in chambers that had grown deaf to their particular anguish.

We never learned of them in our classrooms, these ghosts of empire who were transported like cargo to build other people's dreams. Their names were not written in our textbooks, their sacrifices not commemorated in our national memory. They became India's forgotten children, orphaned not by circumstance but by collective amnesia.

Their stories carry a weight that should bend the very sky—tales of families torn apart by contracts signed in desperation, of languages slowly dying in foreign throats, of festivals celebrated in exile while the homeland forgot the sound of their prayers. They are the proof of empire's cruelty, yet they remain shadows in our understanding of colonial history.

In recognizing their pain, I see my own displacement in perspective. My rootlessness is a gentle drift compared to their violent uprooting. My search for belonging is a luxury afforded by proximity to home. Yet in their endurance, I find something profound—the indestructible nature of human hope, the way identity persists even when everything else is stripped away.

These forgotten journeys remind us that belonging is not just about geography or citizenship papers. It lives in the songs we sing to our children, the spices we use to flavor memory, the prayers we whisper in languages that refuse to die. It survives in the stubborn persistence of love across oceans and decades, in the way heritage adapts and persists even in the most hostile soil.

Perhaps it is time we remembered these lost children of India, these Tamils who were scattered like seeds across the world's plantations. Their stories deserve to be told, their struggles acknowledged, their contributions to distant lands honored. They are part of our history, these forgotten journeys—not footnotes in the margins but central chapters in the epic of human resilience.

In their scattered presence across the globe, they carry something eternally Tamil, eternally Indian, even as they build new identities in new lands. They are living bridges between worlds, testimonies to both the cruelty of empire and the unquenchable spirit of survival.

Their forgotten journeys are also our journeys, their displacement a mirror to our own search for belonging in an ever-changing world.